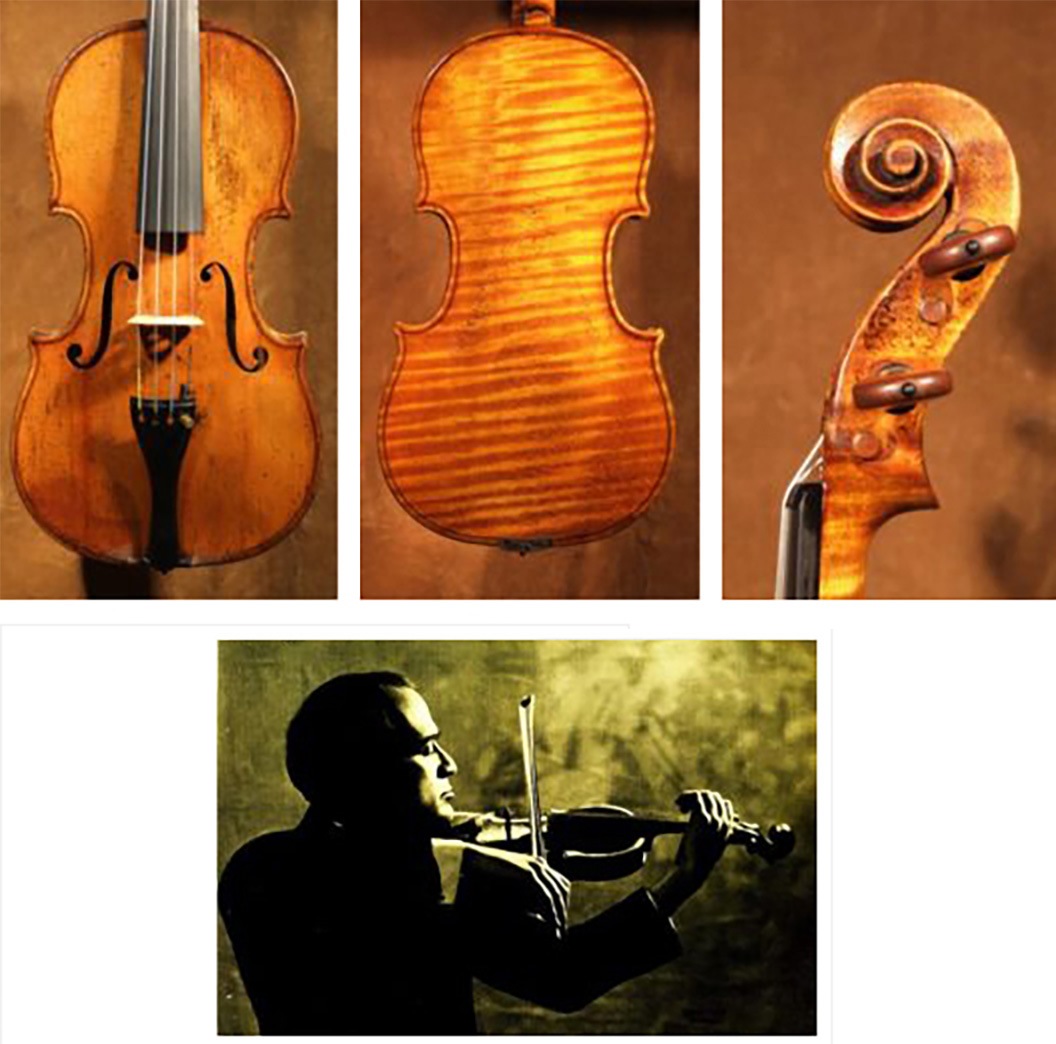

Made in the workshop of Schweitzer in Germany, around 1850.

THE AUSCHWITZ VIOLIN

This instrument was originally owned by an inmate who played in the men’s orchestra at the concentration camp in Auschwitz. And survived.

Abraham Davidowitz, who fled Poland to Russia in 1939, later returned to post-war Germany and worked for the Joint near Munich, Germany, helping displaced Jews living in DP (Displaced People) camps. One day a sad man approached Abraham and offered him his violin, as he had no money at all. Abraham paid 50 $ for the violin, hoping that his little son, Freddy, will play it when he grows up.

Many years later Freddy heard about the Violins of Hope project of the Weinsteins and donated his instruments to be fully restored and come back to life. Since then this violin, now restored to perfect condition, has been played in concerts by the best musicians all over the world. Almost.

It is important to note that such instruments were very popular by Jews in Eastern Europe, as they were relatively cheap and made for amateurs. This particular violin was made in Saxony or Tirol in a German workshop. It carries a false label: J.B. Schweitzer, who was a famous maker in his day.

THE BIELSKI VIOLIN

A Kleizer instrument with a mother of pearl star of David. A German made instrument, probably around 1870.

This is a klezmer’s violin. Most klezmers were self-made and self-taught musicians with a natural talent for music. While many arts were not encouraged by Jewish tradition, music became one of the very few venues available to artists.

It was quite common to young children to play violins, as told by I.L. Peretz, the Yiddish writer, who wrote in one of his short stories that one could tell how many boys were in a Jewish family – by counting the number of violins hanging on the wall.

This is probably the reason why so many klezmer instruments were decorated with the most known Jewish symbol – a Star of David. Most klezmer violins were cheap, made in Czechoslovakia or Germany, in shops that specialized in making ornamented violins.

The klezmer tradition was almost lost during WW2, but lately there is some revival in Europe as well as in Israel and the US.

The restoration work of this violin is dedicated to the Bielski partisans who lived, fought and saves 1230 Jews during the war. Assaela Weinstein, Amnon’s wife is the daughter of Asael Bielski, one of the three brothers who formed the Bielski brigade in Belarus.

THE ERICH WEININGER VIOLIN

A Kleizer instrument with a mother of pearl star of David. A German made instrument, probably around 1870.

This is a klezmer’s violin. Most klezmers were self-made and self-taught musicians with a natural talent for music. While many arts were not encouraged by Jewish tradition, music became one of the very few venues available to artists.

It was quite common to young children to play violins, as told by I.L. Peretz, the Yiddish writer, who wrote in one of his short stories that one could tell how many boys were in a Jewish family – by counting the number of violins hanging on the wall.

This is probably the reason why so many klezmer instruments were decorated with the most known Jewish symbol – a Star of David. Most klezmer violins were cheap, made in Czechoslovakia or Germany, in shops that specialized in making ornamented violins.

The klezmer tradition was almost lost during WW2, but lately there is some revival in Europe as well as in Israel and the US.

The restoration work of this violin is dedicated to the Bielski partisans who lived, fought and saves 1230 Jews during the war. Assaela Weinstein, Amnon’s wife is the daughter of Asael Bielski, one of the three brothers who formed the Bielski brigade in Belarus.

THE FEIVEL WININGER VIOLIN

Made by Brother Placht workshop in Schonbach, Germany around 1880.

Feivel Wininger (far right) with his band “Freedom to the Homeland,” ca.1945. His daughter, Helen, is sitting in front of the bass drum looking up at her father.

The Feivel Wininger violin is a klezmer’s violin. Most klezmers were self-made and self-taught musicians with a natural talent for music. While many arts were not encouraged by Jewish tradition, music became one of the very few venues available to artists.

It was quite common to young children to play violins, as told by I.L. Peretz, the Yiddish writer, who wrote in one of his short stories that one could tell how many boys were in a Jewish family – by counting the number of violins hanging on the wall.

This is probably the reason why so many klezmer instruments were decorated with the most known Jewish symbol – a Star of David. Most klezmer violins were cheap, made in Czechoslovakia or Germany, in shops that specialized in making ornamented violins.

The klezmer tradition was almost lost during WW2, but lately there is some revival in Europe as well as in Israel and the US.

The restoration work of this violin is dedicated to the Bielski partisans who lived, fought and saves 1230 Jews during the war. Assaela Weinstein, Amnon’s wife is the daughter of Asael Bielski, one of the three brothers who formed the Bielski brigade in Belarus.

THE FRIEDMAN VIOLIN

This is a typical story of a Jewish family in Romania. Two sisters, 9 and 11 shared the same violin. Both took music lessons with a nice teacher while their mother watched over and made sure they practice every day. During the war, being transported from one place to another, they lost touch with their parents who kept the violin as a souvenir of their little talented girls.

When the war ended the girls were taken by Aliyat HaNoar (children immigration organization) and sent by boat to Palestine. But this was not the end of their travels and troubles. British police, then in control of Palestine, sent the boat and all immigrants to a camp in Cyprus. Months later the sisters were reunited with their parents and the long gone violin when they arrived in Israel with thousands other survivors who were interned in Cyprus until the establishment of the state of Israel in May 15th, 1948.

THE HAFTEL VIOLIN

Photo: Bronislav Hubermann

Violin was made by AugustDarte in Mirecourt, France around 1870.

This violin belonged to Zvi Haftel, the first concert master of the Palestine Orchestra, later to become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, IPO. It is a French instrument made by a famous maker: August Darte in the town of Mirecourt around 1870.

Heinrich (Zvi) Haftel was one of about 100 musicians gathered by Bronislav Hubermann all over Europe in 1936 and brought to Palestine. Haftel was a distinguished violinist before the war and joined Hubermann after he lost his job in a German orchestra. Hubermann’s vision to create an-all-Jewish orchestra in Palestine saved the lives of many musicians and their families.

Haftel’s violin is one of the best in the collection of Violins of Hope.

THE JACOB HAKKERT VIOLIN

Mirecourt, France 1906

This is the first hand-made violin by a famous Dutch Jewish maker, Jacob Hakkert, who studied in the violin makers’ school in Mirecourt, in the north of France. He joined the family business shop in Rotterdam, Holland, around 1910. Hakkert was an active maker who made violins, violas and cellos. He also had a reputation for developing and selling good quality strings which were popular among many musicians.

Hakkert was deported to Auschwitz where he died on May 22, 1944.

THE TRAIN VIOLIN

Made in Germany around 1900.

In July 1942, thousands of Jews were arrested in Paris and sent by cattle trains to concentration camps in the East, most of them to Auschwitz. On one of the packed trains was a man holding a violin. When the train stopped somewhere along the sad roads of Lyon, France, the man heard voices speaking French. A few men were working on the railways and others walking at leisure. The man in the train cried out,

“To the place where I now go – I don’t need a violin. Here, take my violin so it may live!”

The man threw his violin out of the narrow window. It landed on the rails and was picked up by one of the French workers. For many years, the violin had no life. No one played it.

Years later, the worker passed away and his children found the abandoned violin in the attic. They soon looked to sell it to a local violin maker in the South of France and told him the story they heard from their father. The French violin maker heard about the Violins of Hope and gave it to Amnon Weinstein so that the violin would live.

THE MORPURGO VIOLIN

A refugee violin.

A few years ago a 90-something years old lovely lady and her three daughters came to Weinstein’s workshop in Tel Aviv. Seniora Morpurgo and her daughters brought us the much treasured violin of Gualtiero Morpurgo, the head of the family from Milan, Italy.

The Morpurgos are an ancient and respected Jewish family. They go back some 500 years in the north of Italy. When still a young child, Gualtiero’s mother handed him a violin:

“You may not become a famous violinist, but the music will help you in desperate moments of life, and will widen your horizons. Do not give up, sooner or later it will prove me right”.

That moment arrived without warning. Gualtiero’s mother was forced to board the first train, wagon 06 at the Central Station in Milan. Destination: Auschwitz. Her son, Gualtiero was sent to a forced labor camp and loyal to his mother – took the violin along and often found hope and strength while playing Bach’s Partitas with frozen fingers after a long day’s work in harsh conditions.

Born in Ancona, Gualtiero graduated engineering school and worked in the shipyards of Genoa. When the war ended he volunteered to use his engineering skills to build and set up ships for Aliya Bet, helping survivors of the war sail illegally to Palestine. For this he was awarded in 1992 the Medal of Jerusalem by Yitzhak Rabin.

Gualtiero never stopped playing. He was 97 when he could play no more and put his life-long companion in its case. After his death in 2012 his widow and three daughters attended the Violins of Hope concert in Rome and decided that this is where it belongs – in the hands of devoted musicians in fine concert halls.

THE MOSHE WEINSTEIN VIOLIN

Violin made by Johann Gottlieb Ficker, around 1800.

Right photo: Moshe and Zehave (Golda) Weinstein

This violin was a life-long friend of first-generation violin maker Moshe Weinstein. Born in a shtetl in Eastern Europe, little Moishale fell in love with the sound of the violin. It happened when a klezmer troupe arrived in his small town to play at a rich man’s wedding. While all the children gathered under the table to hide and steal sweets, Moishale was hypnotized by the sound of music. After a few festive days, the troupe left, and so did Moishale, who followed the musicians out of town. His mother, Ester, looked for the boy, but to no avail.

When his mother finally found him and dragged him back home, he was first punished and then was given a very simple violin. This was the turning point in the family’s history.

Moishale taught himself to play; he later studied at the music academy in Vilna, where he met a pianist named Golda. The two later married and immigrated to Palestine in 1938.

Before leaving Europe, Moshe Weinstein went to Warsaw to study the repair of stringed instruments with Yaacov Zimermann. Since many Jews played the violin, Moshe felt there would be need for a violin maker in Palestine.

Upon his arrival in Palestine, Moshe worked in an orchard picking oranges. A year later, he opened a violin shop in Tel Aviv.

Loyal to the tradition of helping young prodigies with their fist steps into music, Moshe supported many talented Israeli children, among them: Shlomo Mintz, Pinchas Zukerman, Yitzhak Perlman, and others.

THE ZIMERMANN-KRONGOLD VIOLIN

Violin, Warsaw, 1924

Photo on right: Shimon Krongold at his music room, Warsaw.

Yaacov Zimermann was one of the first Jewish violin makers in Warsaw. Shimon Krongold was a wealthy industrialist there and an amateur violinist, who ordered a violin made by Zimermann. Zimermann made him a fine instrument with a lovely Star of David inlaid on the back. Inside the violin he glued a label in Yiddish:

I made this violin for my loyal friend Shimon Krongold , Yaacov Zimermann, Warsaw, 1924.

When war broke in 1939 Shimon managed to escape to Russia and ended up in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where he died of typhus towards the end of the war. A few years later a survivor from Tashkent came to the Krongold family in Jerusalem with the story of his death and a violin in hand. Shimon was the uncle of the Krongolds in Jerusalem, who paid for the violin and kept it in memory of their uncle.

It is important to note that before the war Shimon Krongold helped some Jewish prodigal children, among them Michel Swalbe, who used to get music lessons in Krongold’s home. Swalbe later became the leading violinist of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and remembered Krongold as his benefactor.